Features

The code is very flexible and can easily be extended to include new setups

and algorithms. Some of the implemented features are presented below:

Particle Push

Particle push is the procedure that updates both the position and

velocity of each particle based on the electric and magnetic fields at

the location of the particle. Position and velocity are leap-frogged

over each other, that is they are defined at half a timestep offset from

each other. This makes the scheme second order accurate in time.

Boris Push

Usually the code uses the original Boris push in the relativistic

version as defined in Boris, 1970. (The paper is annoyingly hard to

find. It was titled

Relativistic plasma simulation - optimization of

a hybrid code and was published in the Proceedings of the Fourth

Conference on Numerical Simulation Plasmas.)

Vay Modification

For simulations where particles reach more than mildly relativistic

velocities the code also implements the modifications to the Boris push

that were proposed by

Vay, 2008.

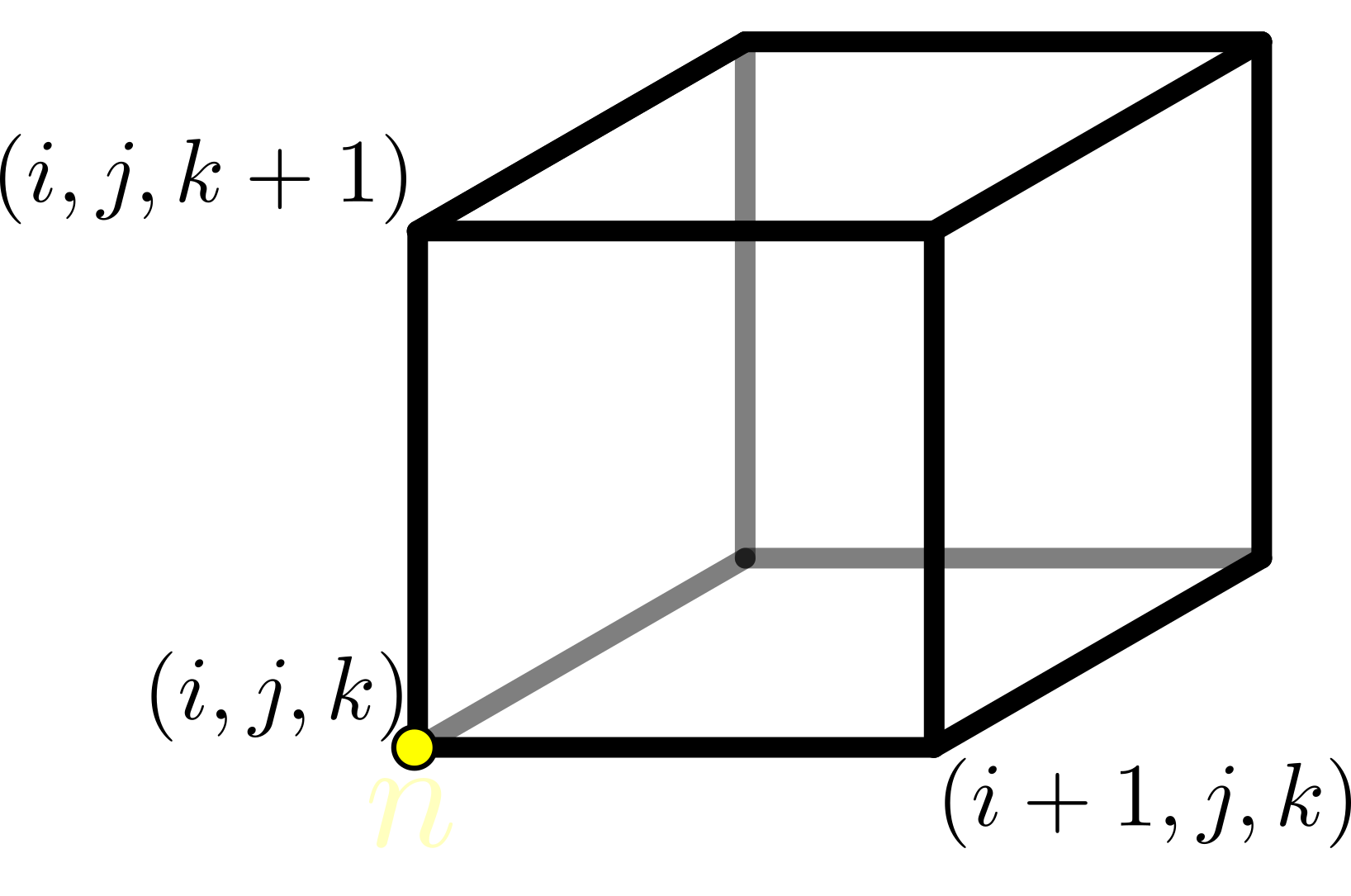

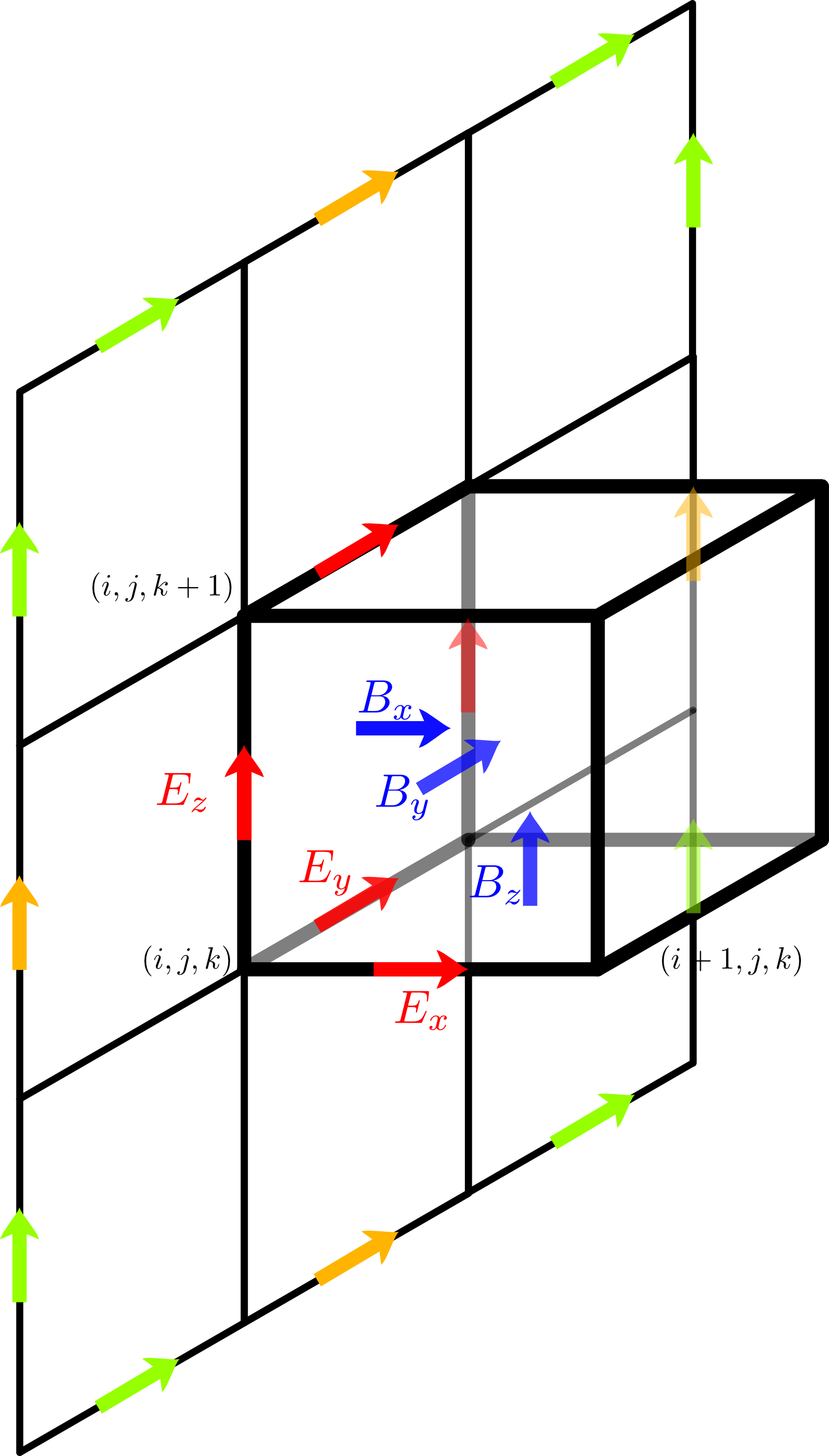

Staggered Grid

Unlike many Eulerian codes that have all components of the fields that

are stored in the grid located at the center of each grid cell, it is

common in particle-in-cell codes to have different field components at

different locations. This is especially useful for the commonly used

electromagnetic plasma model, where the update of the field quantities

in time requires the use of the curl of the dual field. The most widely

used arrangement, which is also used in ACRONYM, is the so called Yee

lattice, as proposed by

Yee, 1966. In

principle the locations of the electric and magnetic fields can be

interchanged without losing the advantageous properties, however we have

decided on the layout shown below, as it makes the implementation of

perfect electric conductors easier.

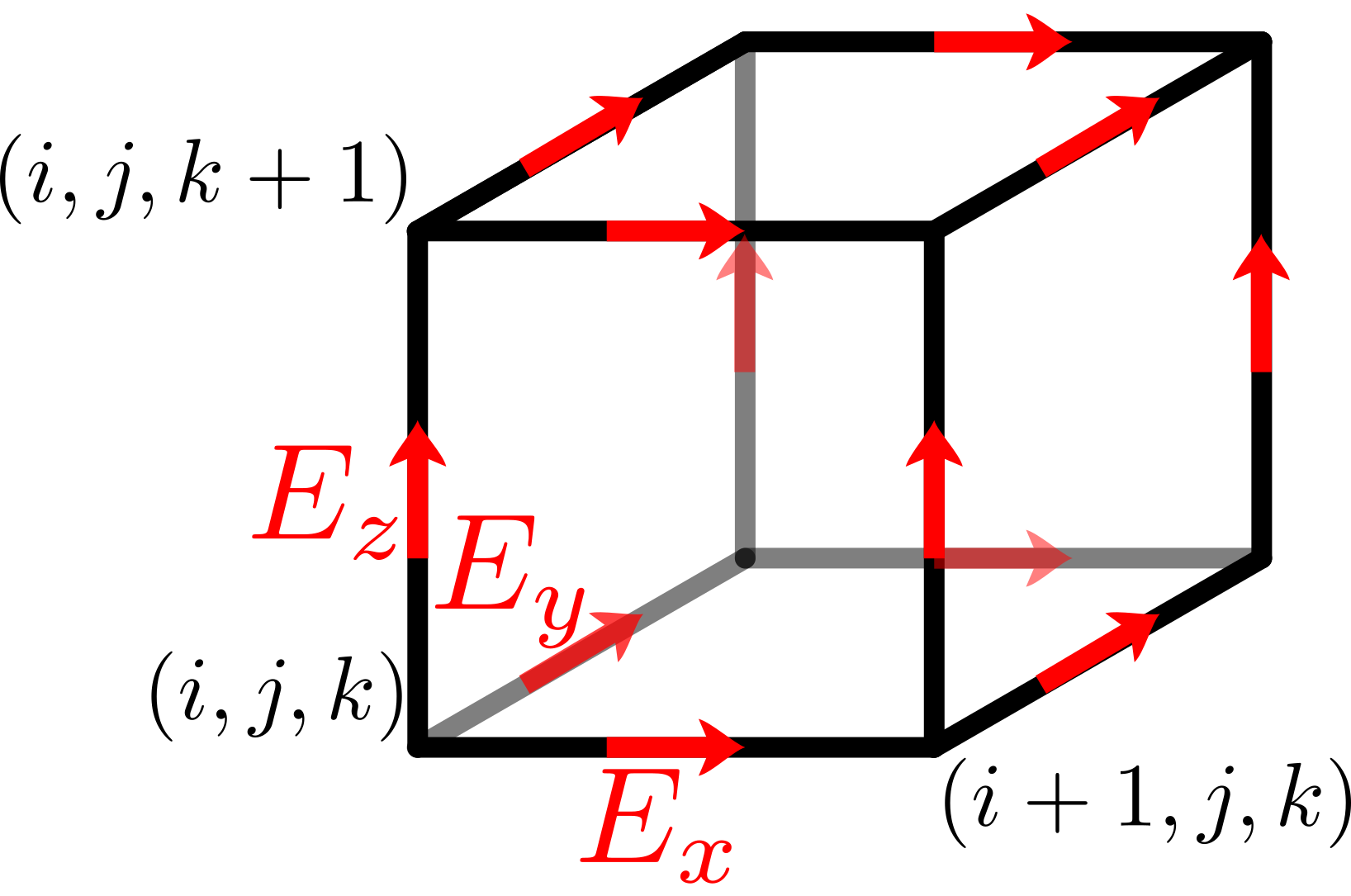

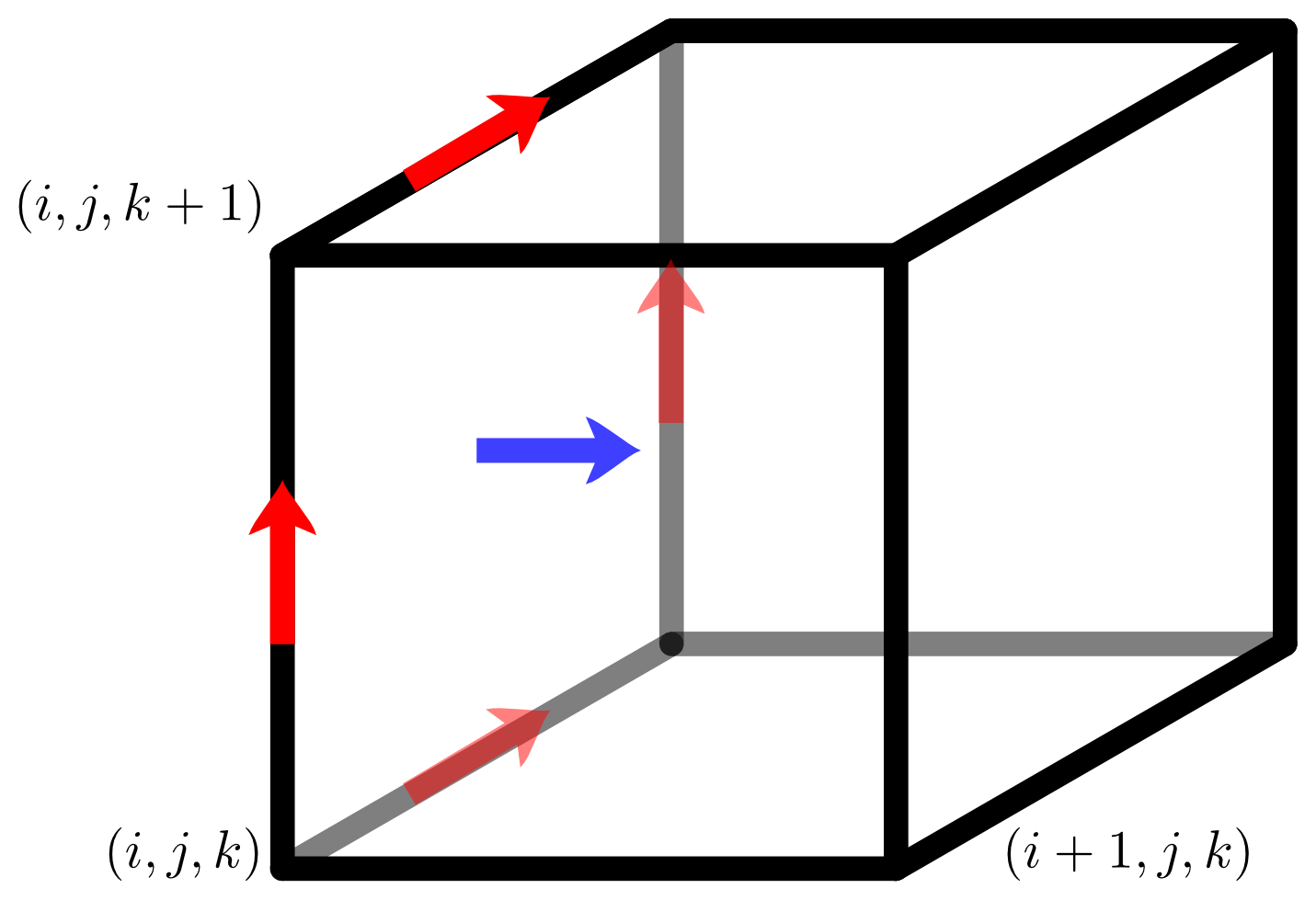

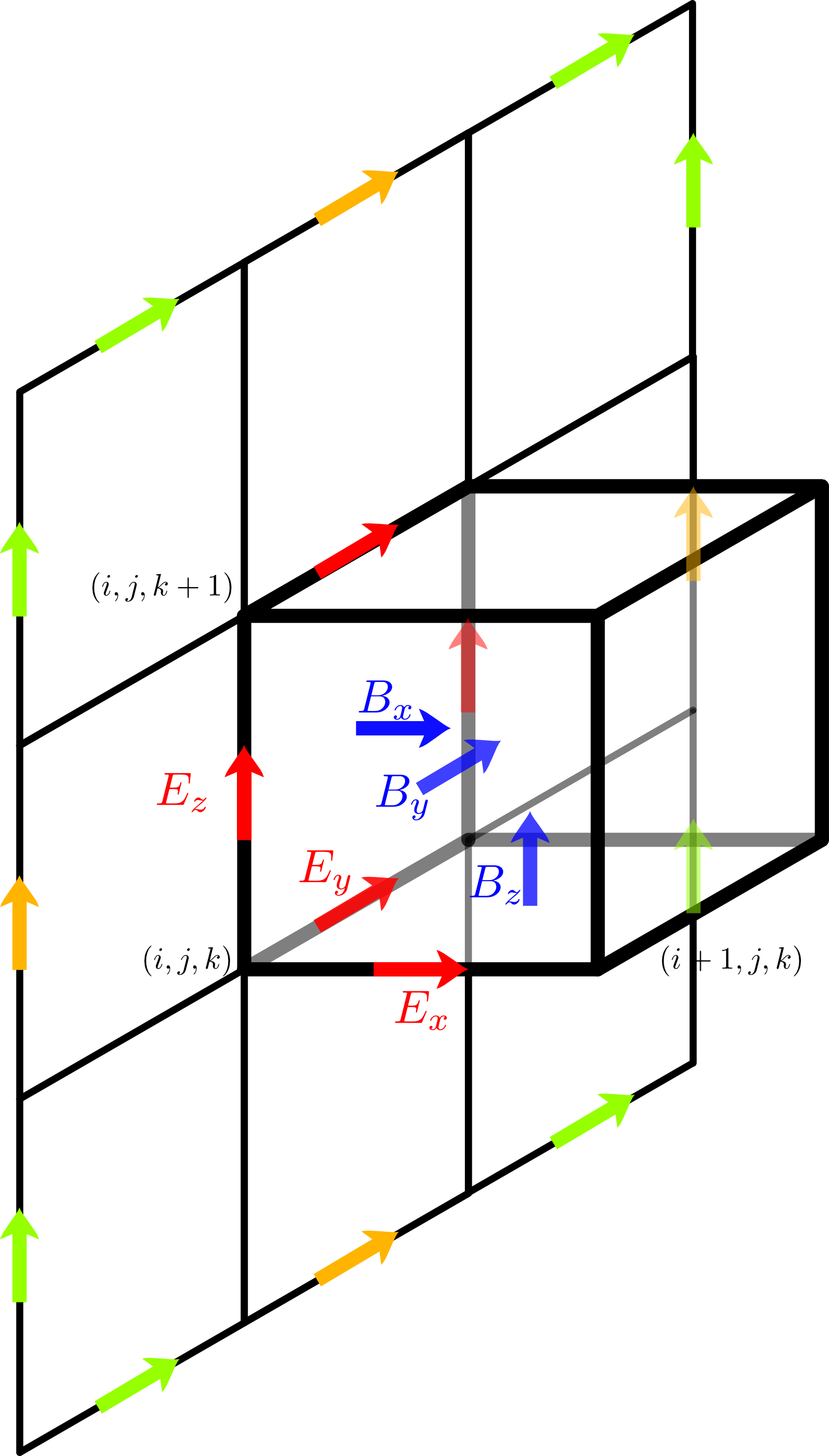

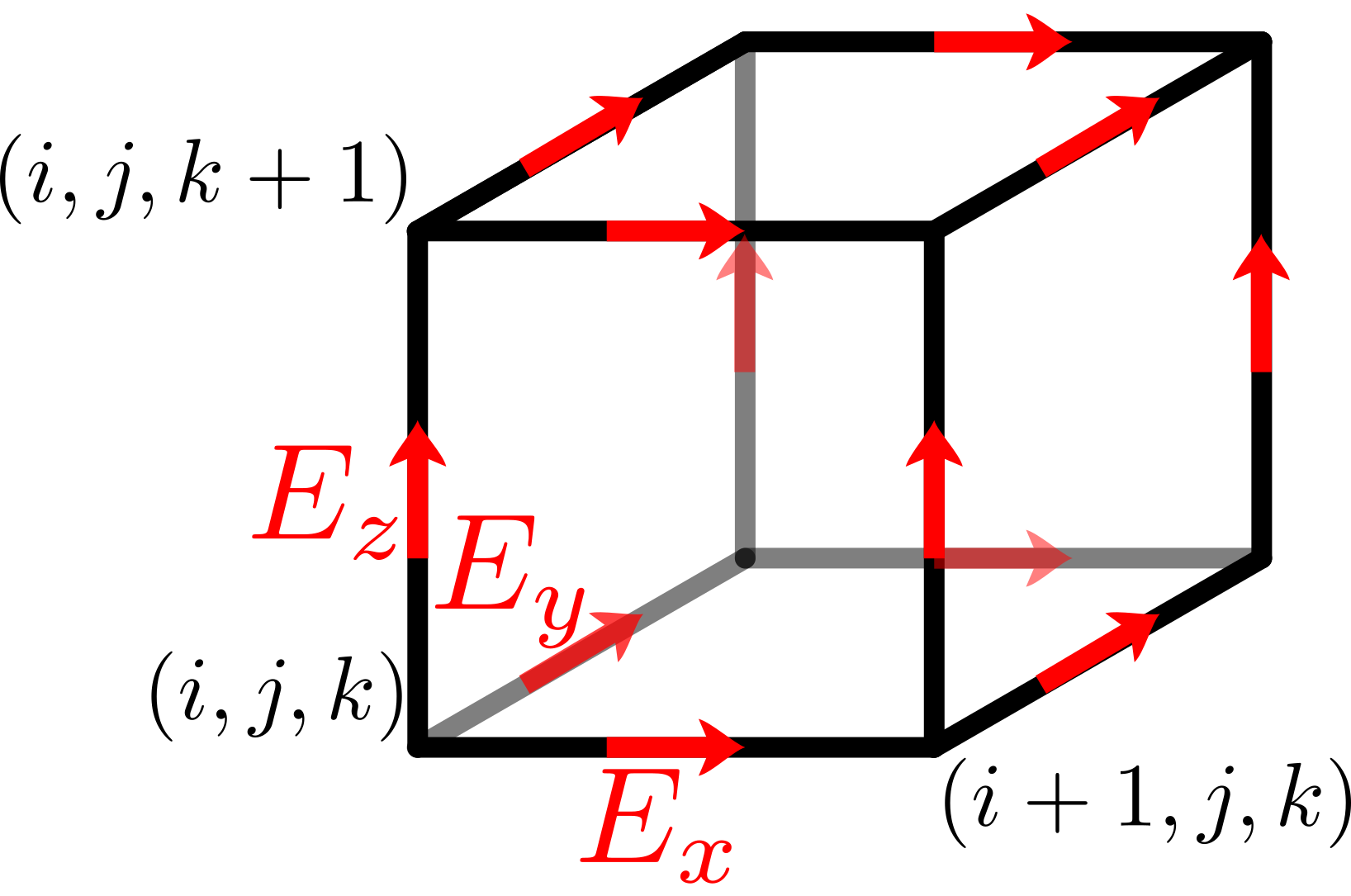

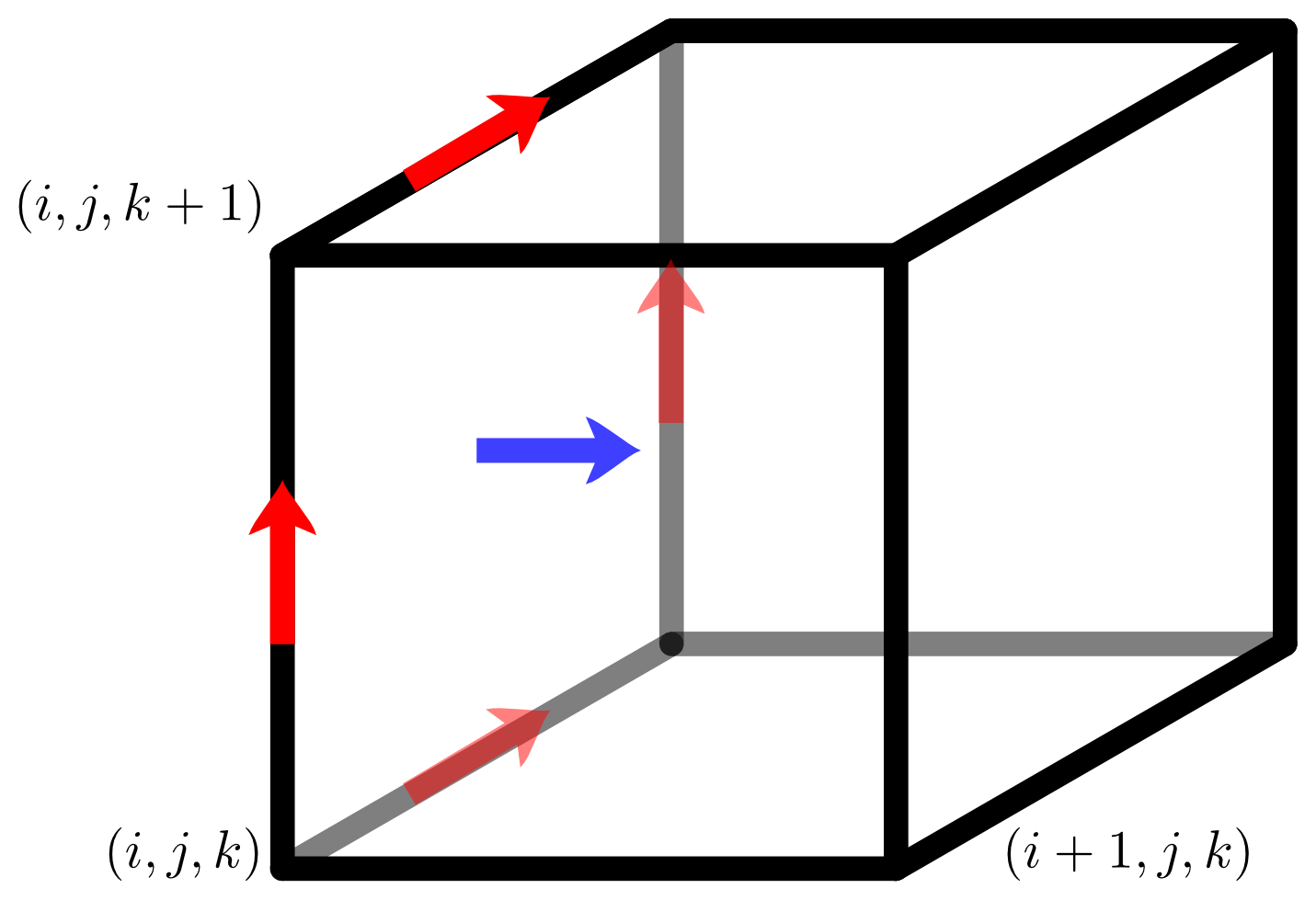

Electric Field

The electric field components are located at grid edges, displaced to

the center of the edge that is aligned with the direction of the field

component. That is the x component E_x of the electric field is

displaced by half a grid spacing dx along the edge e_x.

For a perfectly electrically conducting wall at x=0, this arrangement

locates the y and z component exactly at the surface of the conductor,

where they are trivially forced to zero.

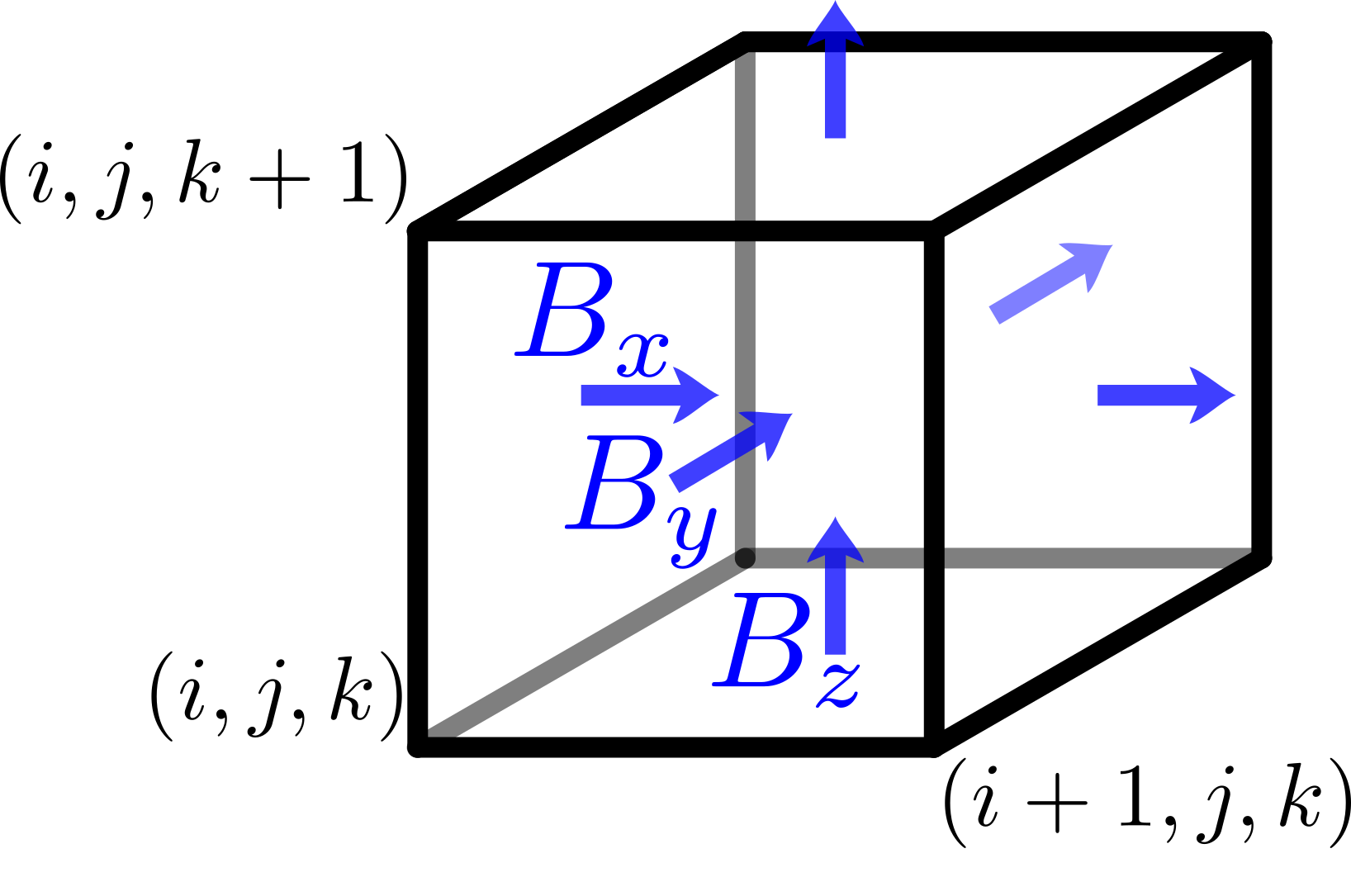

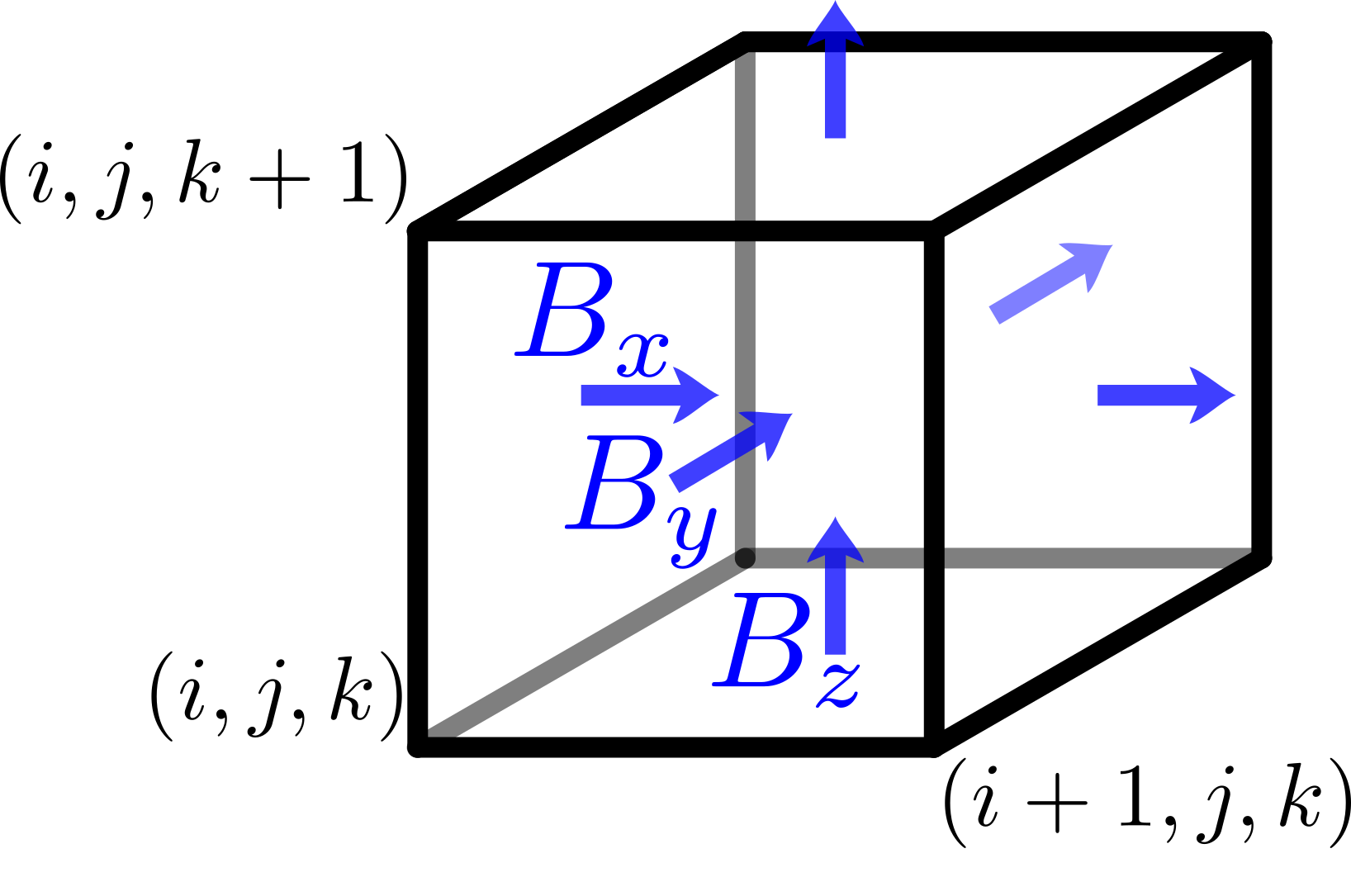

Magnetic Field

The magnetic field components are located on the dual grid, that is on

the cell faces. The x component B_x of the magnetic field is located

at the center of the face defined by e_y and e_z.

Therefore the electric field components E_y and E_z are located on the

cell edges around the magnetic field component B_x, which is optimal

for the calculation of curl(E)_x that is needed to update B_x.

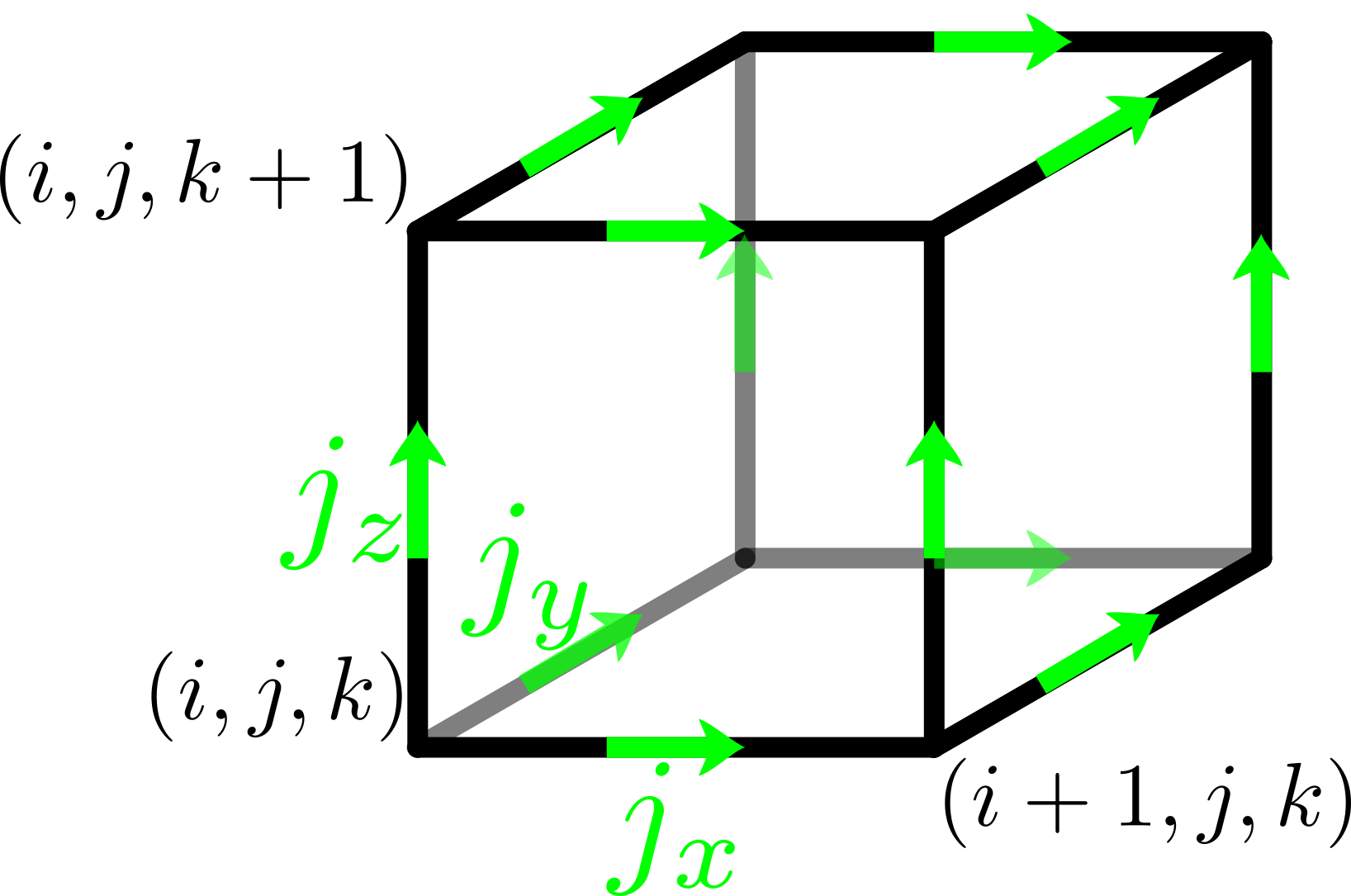

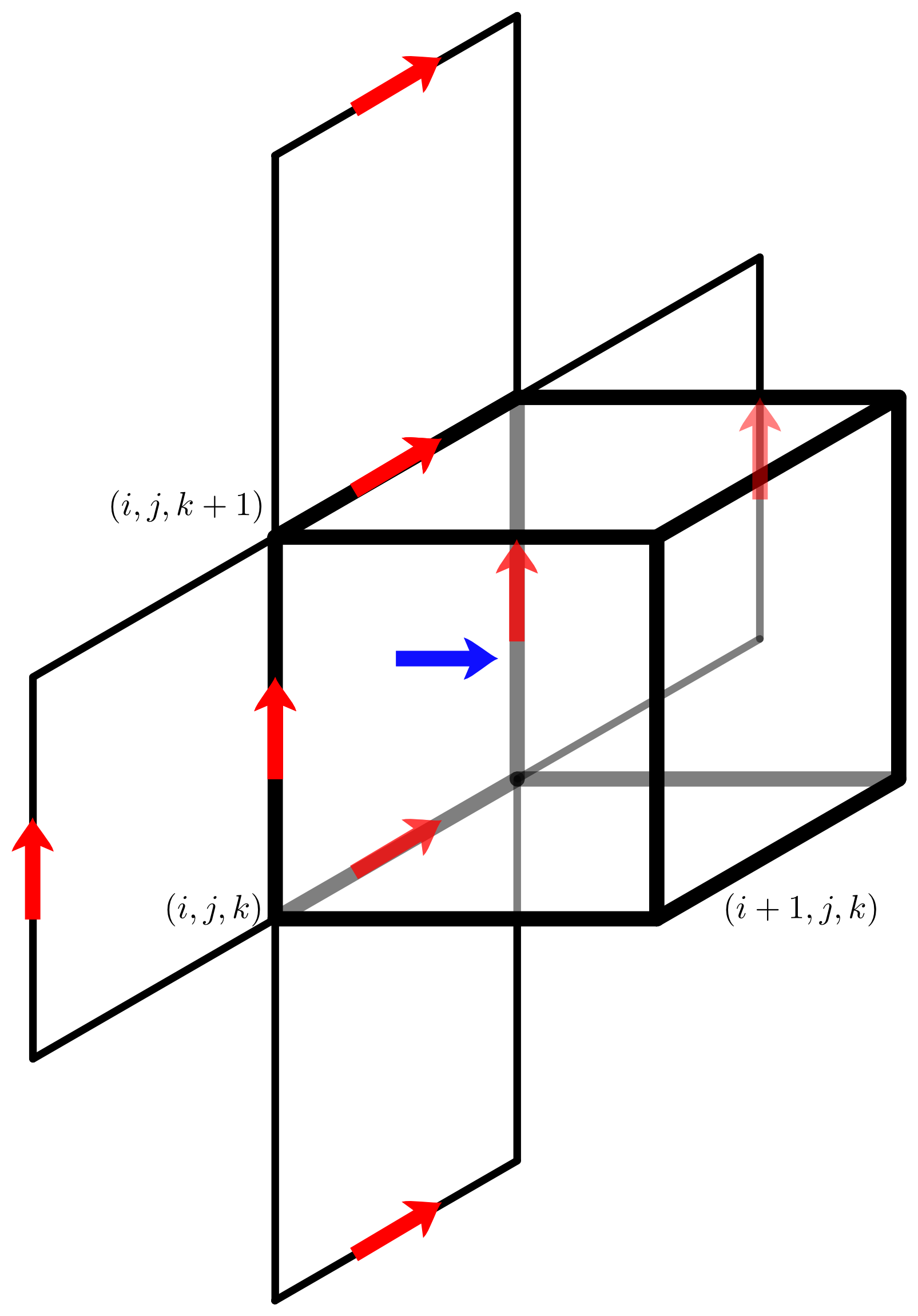

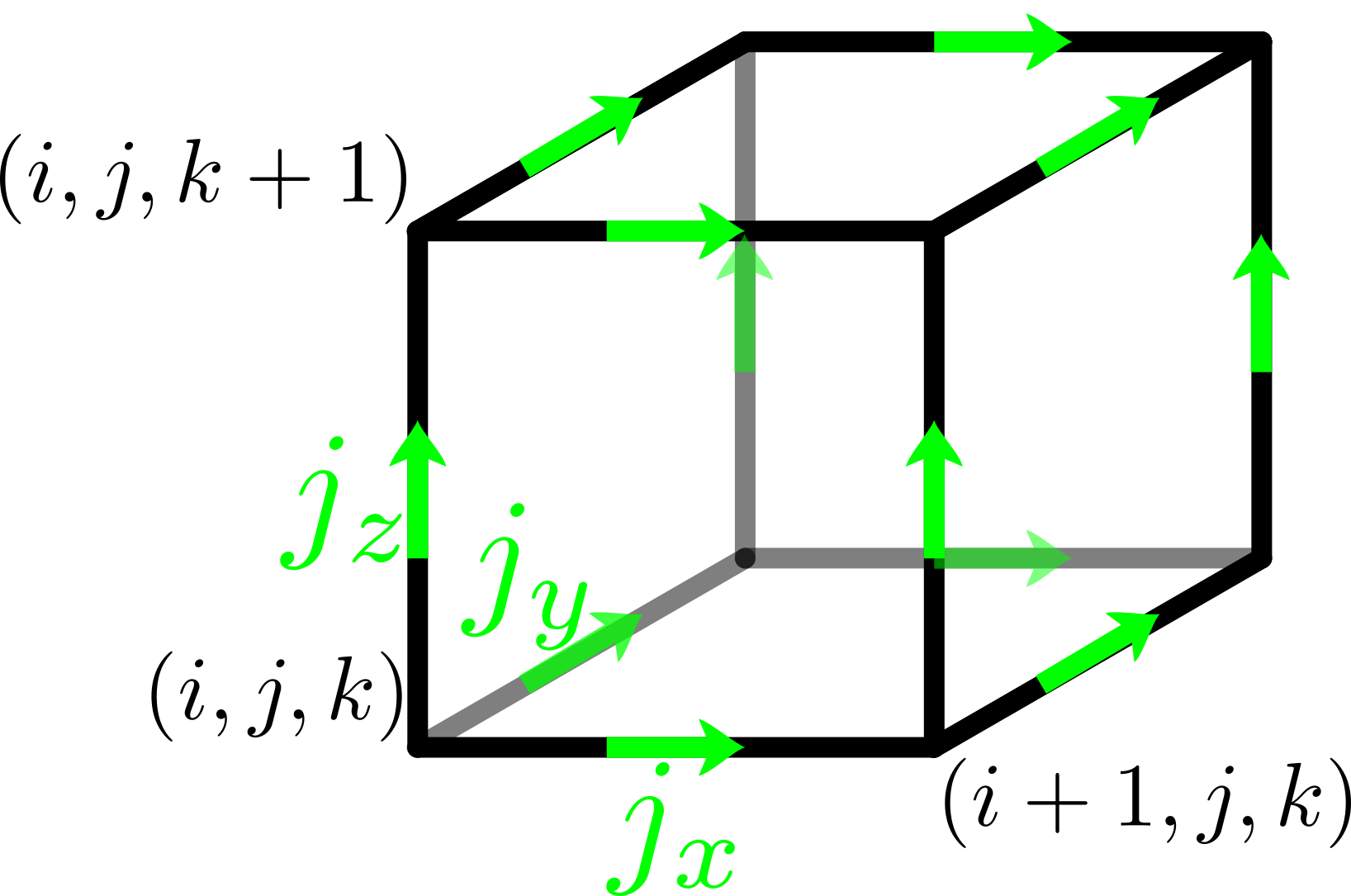

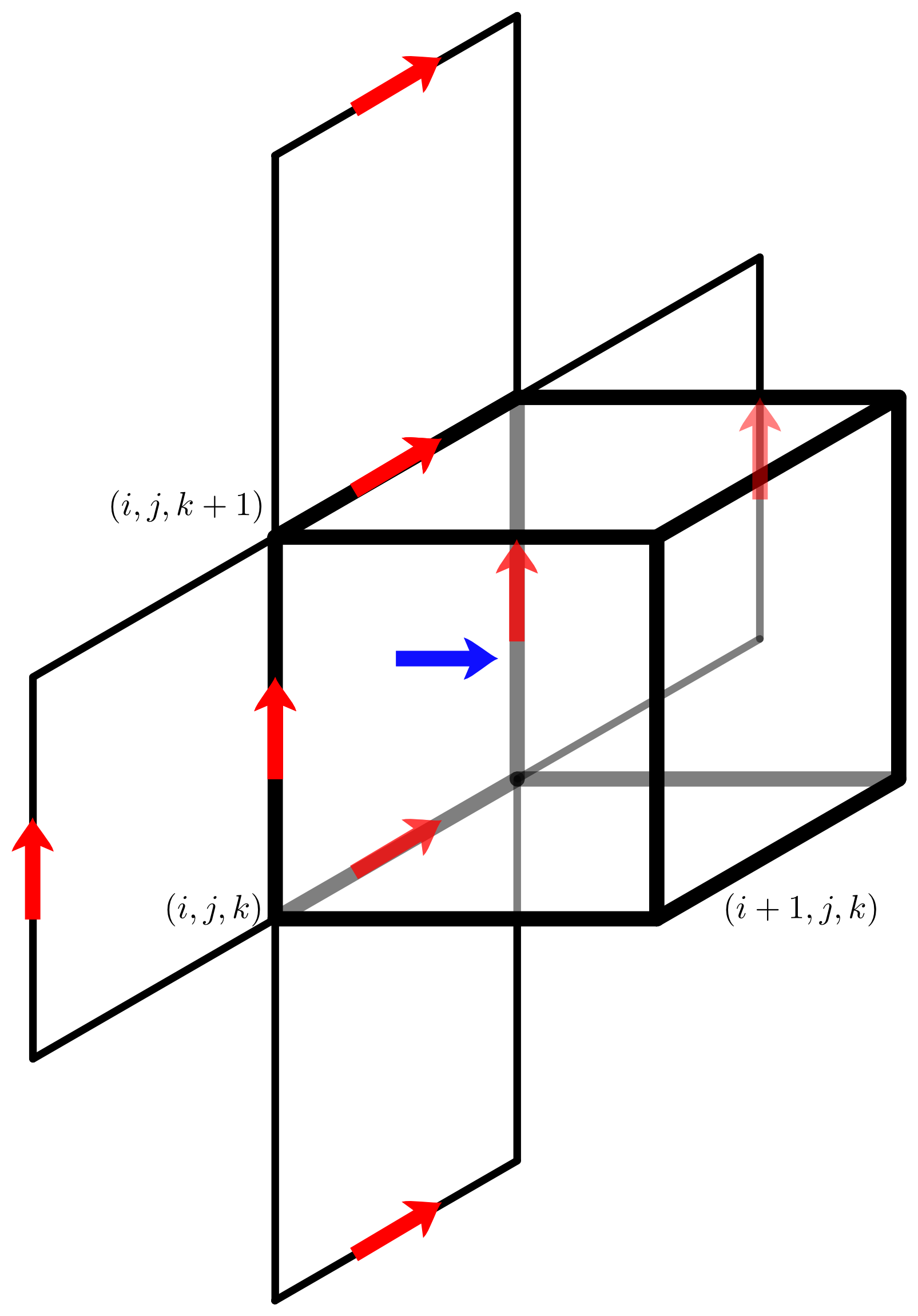

Electric Current

The components of the electric current (and mass flow, if computed for

analysis purposes) are located at the mid points of cell edges.

In the electromagnetic plasma model the update of a component E_i of the

electric field needs the curl curl(B)_i of the magnetic field and the

corresponding component j_i of the current. Therefore it is beneficial

to collocate the current density with the electric field.

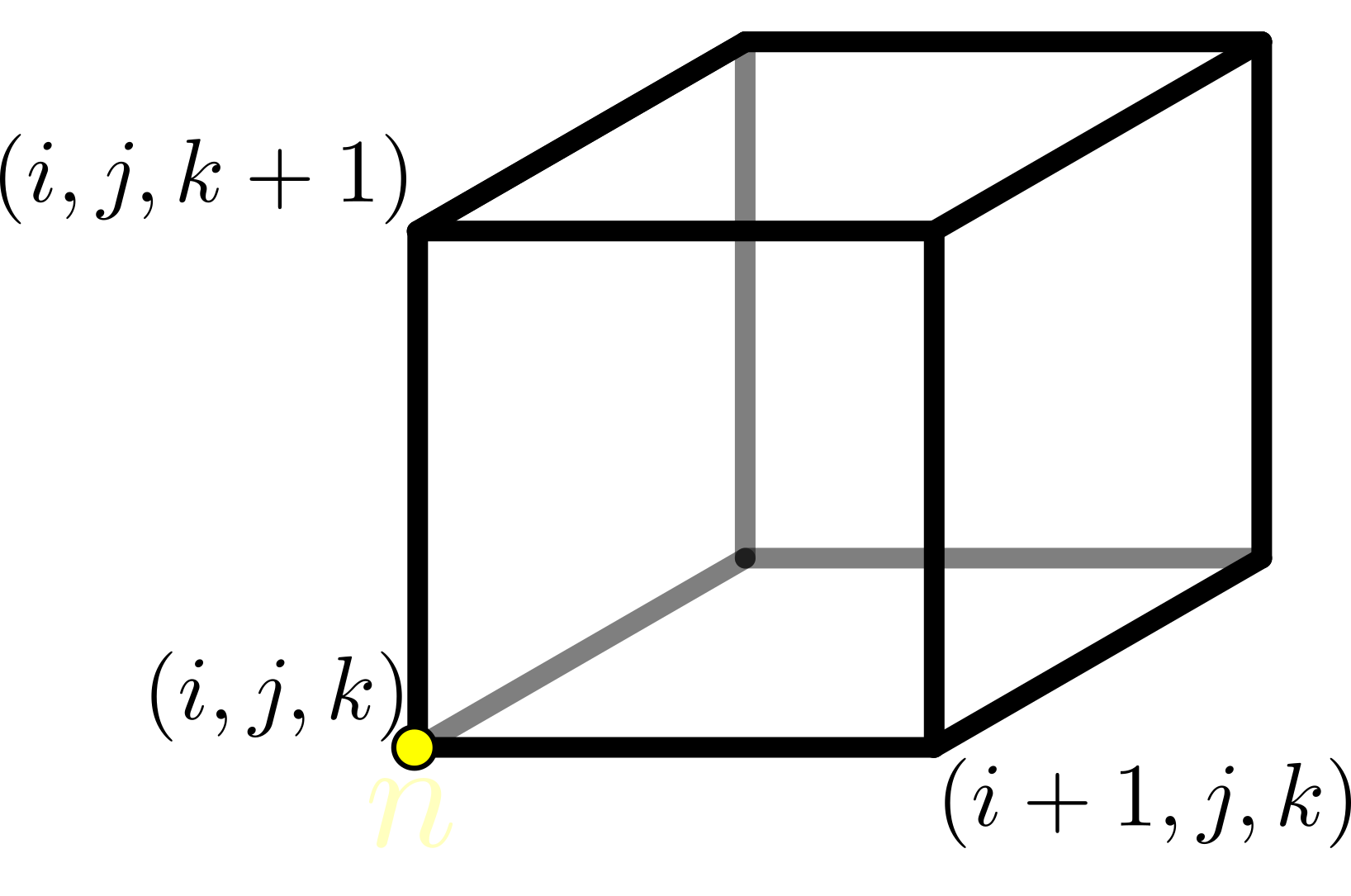

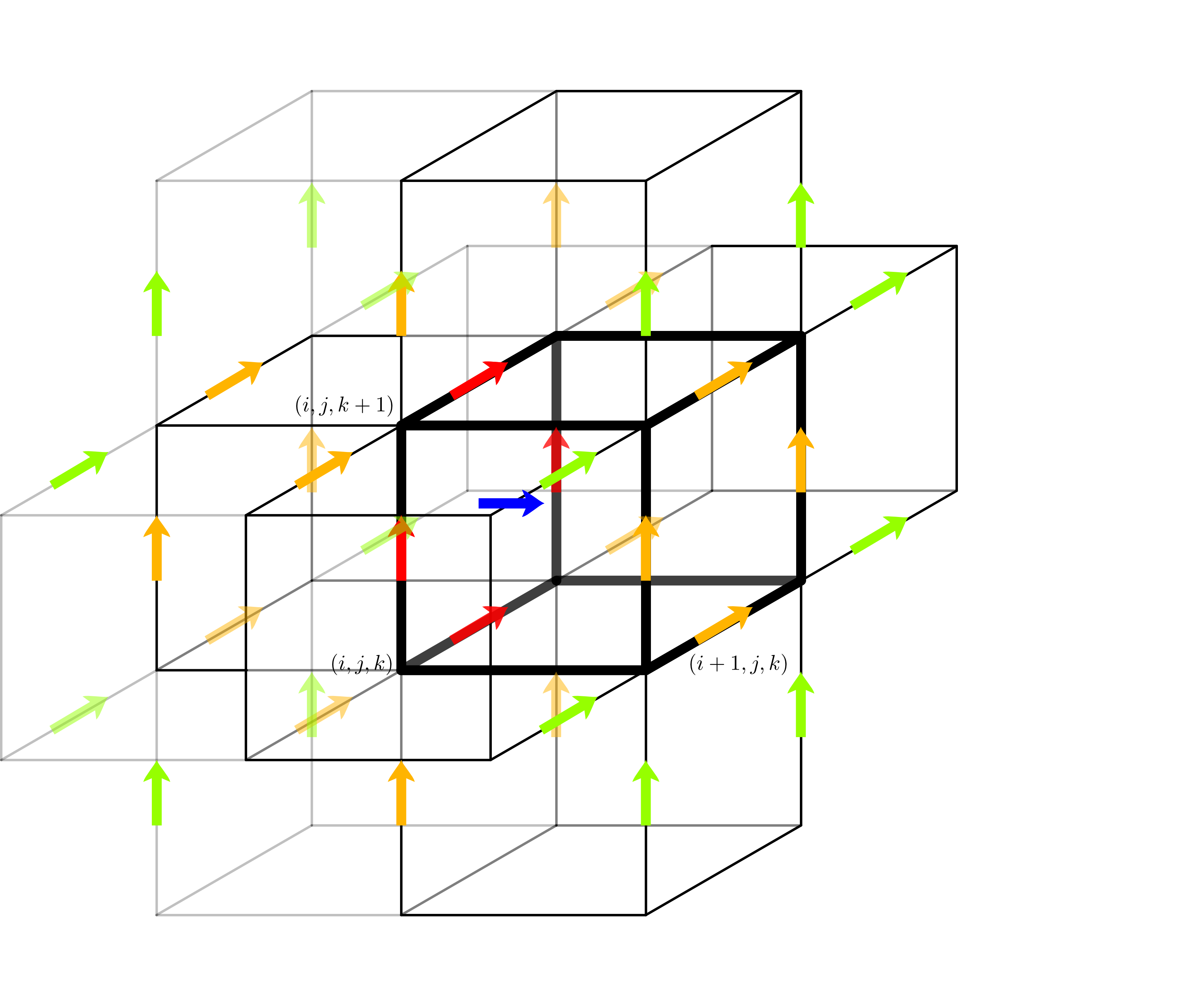

Charge Density

The charge density is located in the corner of the grid cell. The

center of the grid cell would seem more intuitive, as it would then

represent all charges in the cell, but the location in the corner

makes the formulation of the Poisson equation (for the electrostatic

plasma model) and of the discrete continuity equation (when testing the

electromagnetic plasma model) much easier.

Shape Functions

Particle-in-cell codes are, as the name already implies, a mix of an

Eulerian gridded description of the fields and a Langrangian

description of freely moving particles. Connecting the two parts

requires interpolation between the staggered grid described above and

the arbitrary position of a particle. Many different interpolation

schemes have been devised over the years. Schemes that decompose into

products of one-dimensional shape functions can easily be implemented

in ACRONYM and actually a large number of them is supported. The most

commonly used schemes of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd order are shown in a little

bit more detail below. For additional details we refer to the paper

Different Choices of the Form Factor in Particle-in-Cell

Simulations by

Kilian et al., 2013.

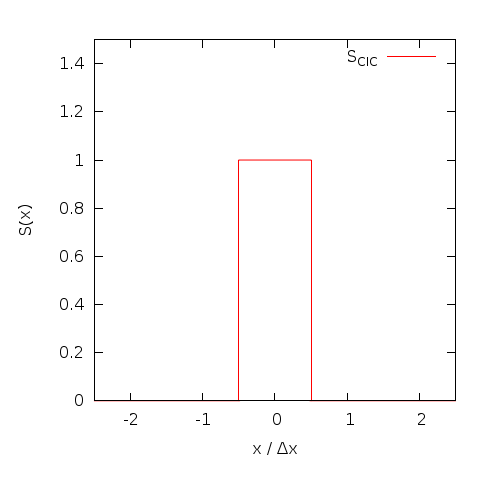

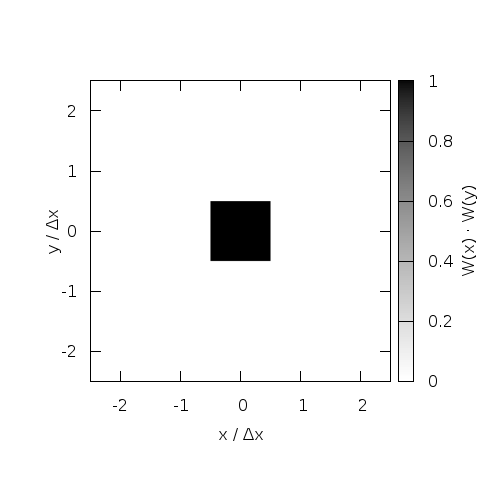

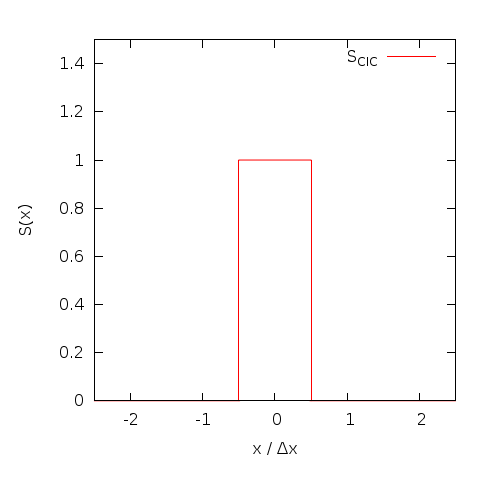

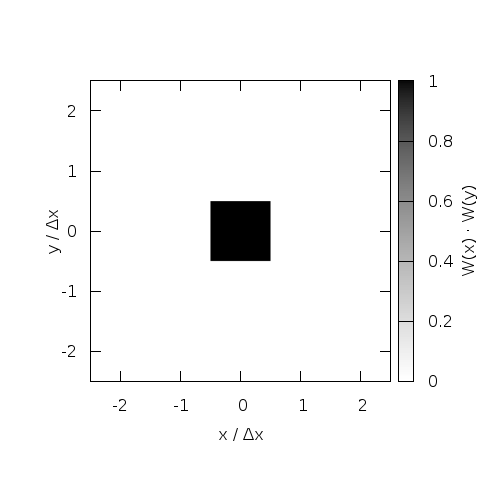

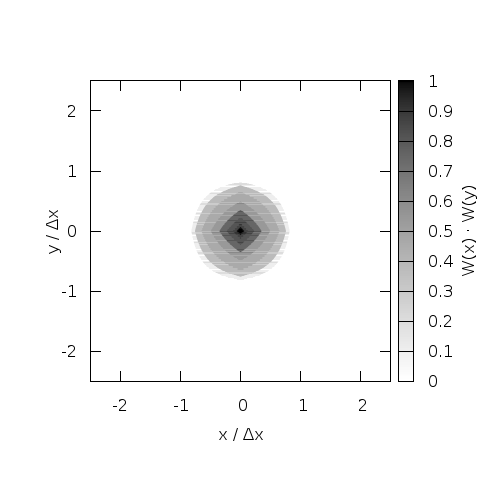

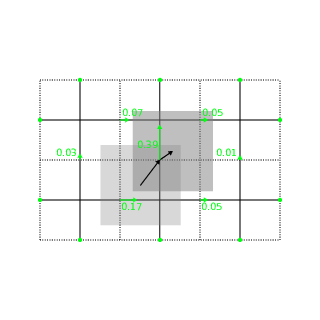

Cloud in Cell

While assigning particles simply to the nearest grid point (NGP) is

possible, this trivial zeroth order interpolation introduces too much

numerical noise to be useful. Assigning a finite size of one grid cell

to particles strongly reduces this noise. The overlap integral between

the charge cloud representing the particle and the grid cell (area

weighting) can be calculated analytically beforehand and the resulting

computation is equivalent to a linear interpolation. This CIC method was

originally introduced by

Birdsall and

Fuss, 1969 and made semi-Langrangian plasma simulations feasible.

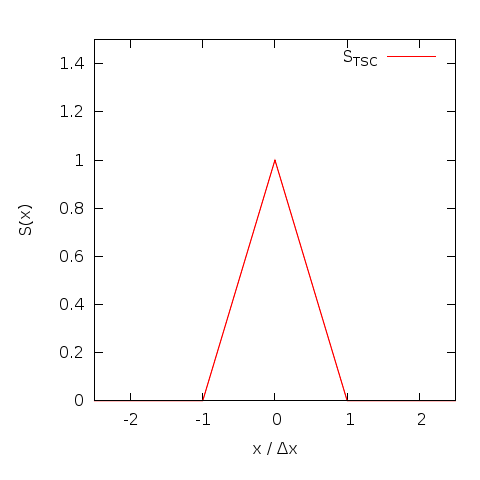

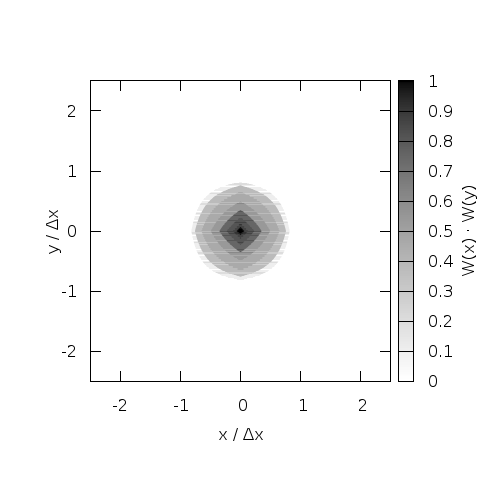

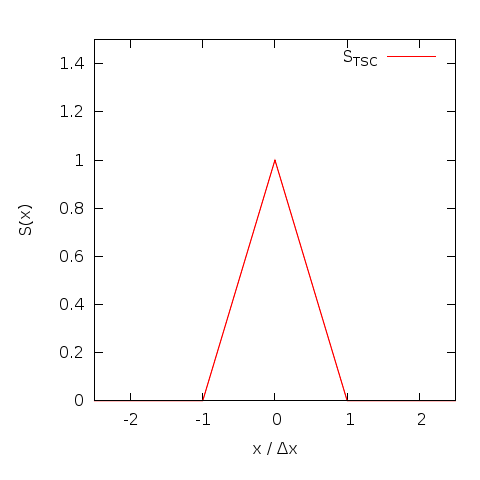

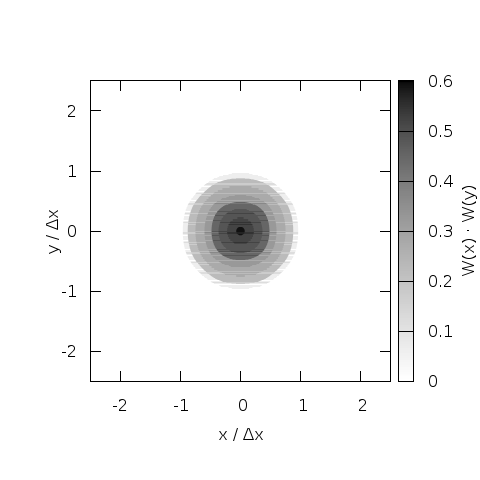

Triangular Shaped Cloud

While CIC is a big improvement over NGP, it is not perfect. A widely

discussed (see e.g. chapter 5 in the standard reference

Computer

simulations using particles by Hockney and Eastwood, 1988)

improvement is the triangular shaped cloud (TSC) that replaces the

piecewise defined cloud of CIC with a continuous, piecewise linear

function. This increases the effective size of the particle and the

number of grid cells involved in the interpolation somewhat, but the

reduced noise level and the improved isotropy usually justifies the cost.

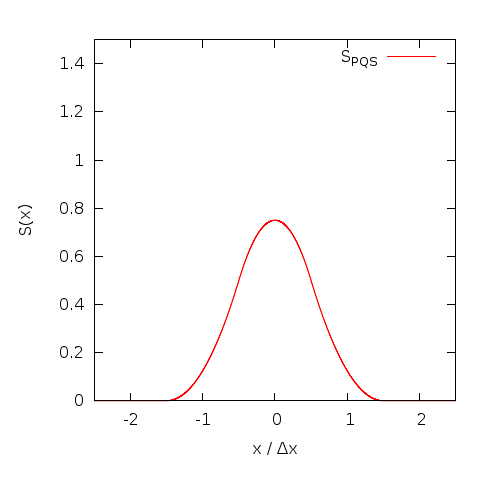

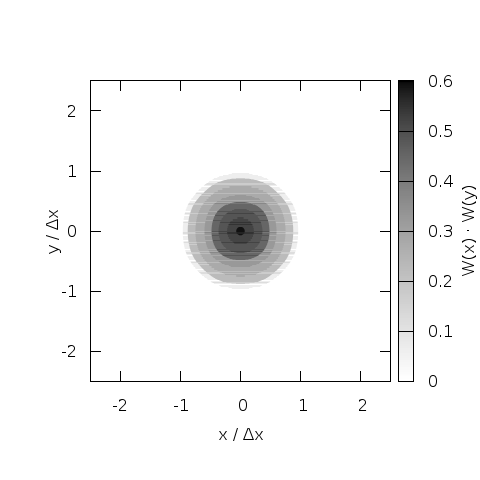

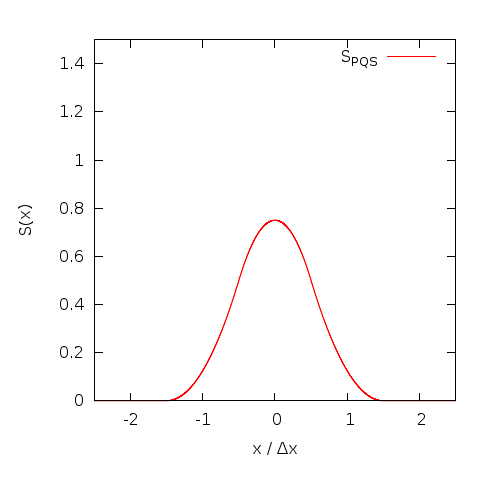

Piecewise Quadratic Shape

The next higher order interpolation function is the piecewise quadratic

shape (PQS), which is not only continuous, but also differentiable. This

improves roll-off of the Fourier transform by 3dB per octave (a function

that has a discontinuity in the nth derivative has a Fourier transform

that rolls of proportional to 1/k^{n+1}). If the additional cost due to

the growing number of grid cells that are involved in the interpolation

is justified depends on the tolerable noise level and the dimensionality

of the problem.

Current Deposition

Charge deposition is relatively straight forward once a shape function

is selected. For an electrostatic particle-in-cell code it is

sufficient to calculate the electric field and continue. An

electromagnetic code on the other hand needs the electric current as a

source term in the Maxwell solver. Naive deposition (interpolating q*v

at the position of the particle using the shape function directly)

leads to a current distribution that does not satisfy the discrete

continuity equation. This in turn leads to ghost charges, violation of

Gauss law and phantom forces. While it is possible to correct the

computed current distribution to remove these effects (and the code

does support divergence cleaning following the scheme by

Marder, 1987)

it is also possible to construct current deposition schemes that

directly conserve continuity of electric charges.

The code supports two different such schemes (details below).

Additionally it can compute and deposit quantities such as mass density,

mass flow, number density, and moments of the distribution function,

both as a total over all species and separated per species. These

quantities are not needed for the temporal evolution, but can be

valuable diagnostics when investigating the physics of a problem.

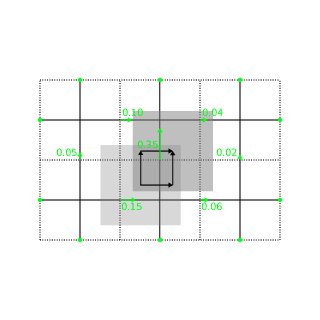

Esirkepov

The default current deposition scheme follows the method proposed by

Esirekepov,

2001. It decomposes the particle motion into axis parallel motions

that are weighted in such a way that the correct total current is

produced and charge conservation is satisfied. This method works with

all shape functions and shows good performance.

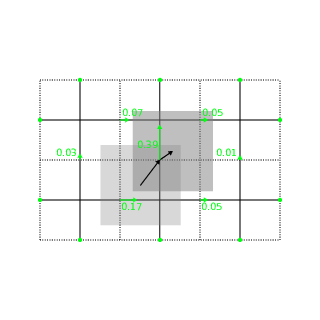

Umeda

Alternatively the code also supports the current deposition algorithm

by

Umeda,

2003. This algorithm decomposes the particle motion into straight

segments with the constraint that the particle can only cross cell

boundaries at the middle of cell faces. Only CIC and TSC shape

functions are supported. It should be possible to extend this to other

shape functions, but to our knowledge this is beyond the published

state of the art. Main advantage of the deposition method is a

different distribution of numerical noise in k-omega space that might

be advantageous to some simulations.

Field Solver

The ACRONYM code supports a large number of different field solvers,

that have different tradeoff between computational cost, numerical

noise, and accuracy. They can be roughly divided into three classes:

Electrostatic solver, where the electric field is determined by the

charge density through Poissons equation; Electromagnetic solver, where

both electric and magnetic fields are updated self consistently from

the current density; and the radiation free plasma model, which neglects

the displacement current and removes electromagnetic waves by

construction. Warm collisionless plasma (in excess of 1 MK) is usually

best handled by the electromagnetic solvers. However if applicable, the

other solvers can speed up the computations by one or two orders of

magnitude, as the restrictive CFL condition on the time step due to

electromagnetic waves is removed.

Electrostatic

In the electrostatic plasma model the (longitudinal) electric field is

determined by the net charge density of all particles. The Poisson

equation that has to be solved is elliptic, i.e. exhibits instantaneous

propagation and requires a global field solver. While surprising at

first this can be thought of as the limit of long timesteps (much longer

than the propagation time of electromagnetic waves through the

simulation domain) or the limit of infinite speed of light. Transverse

electric fields are not present in this model and the magnetic field is

static. This plasma model is only applicable in the absence of large

electric current and (equivalently) slow (certainly non-relativistic)

particle motion. Depending on the boundary conditions (mixed boundary

conditions are not supported in this plasma model) one of two

different solvers is chosen.

Spectral Solver

If the domain is periodic, the Poisson equation of the electrostatic

plasma model is solved using a spectral solver. The code deposits the

charge density of all particles to the grid and computes the Fourier

transform of it. In Fourier space the Poisson equation can easily be

solved for each different k, allowing for the direct construction of

of the Fourier transform of (one component of) the electric field. A

subsequent inverse Fourier transform produces the electric field in

real space. The global Fourier transform over all spatial dimensions

is computed using a modified version of the

Sandia

FFT that allows to use

FFTW 3 as

the underlying local 1d transformation. Two features that are described

in the literature but not used in all codes are the direct computation

of the electric field instead of the potential, which requires two

additional inverse Fourier transformations but provides slightly more

accurate fields, and the use of the so-called sinc softening.

Solver using Greens Functions

If open / absorbing boundaries are desired in the electrostatic model,

a different solver is used. It also uses the charge density, but then

convolves that with the Greens function of free space to determine the

electric field. The convolution is performed in Fourier space, where it

is a simple point by point multiplication. The Fourier transformed of

the charge density is determined directly from the charge density in

each time step. The Fourier transformed of the Greens function is

determined once, at startup by evaluation of an analytic expression for

the Greens function on a double sized (to avoid wraparound in Fourier

space) grid followed by a Fourier transformation. After the convolution

/ multiplication in Fourier space an inverse Fourier transform is

necessary for each field component to determine the electric field in

real space.

Electromagnetic

The most widely used plasma model in ACRONYM is the electromagnetic

plasma model where both electric and magnetic fields are updated

selfconsistently. In the initial setup the electric field is usually

set to zero and the magnetic field is set to some (divergence-free!)

profile determined by the specific setup. In each timestep the electric

field is updated based on the curl of the magnetic field and the

electric current, before the magnetic field is leap-frogged over it

using the curl of the new electric field. (Actually the magnetic field

update is split into two half-steps to have the electric and magnetic

fields available at the same instant in time to update the particles.)

While the details of the calculation of the current density that enters

as a source term is shifted to the current deposition, the numerical

approximation of the curl is retained directly in the electromagnetic

field solver. Different finite differences approximations are

implemented in the code:

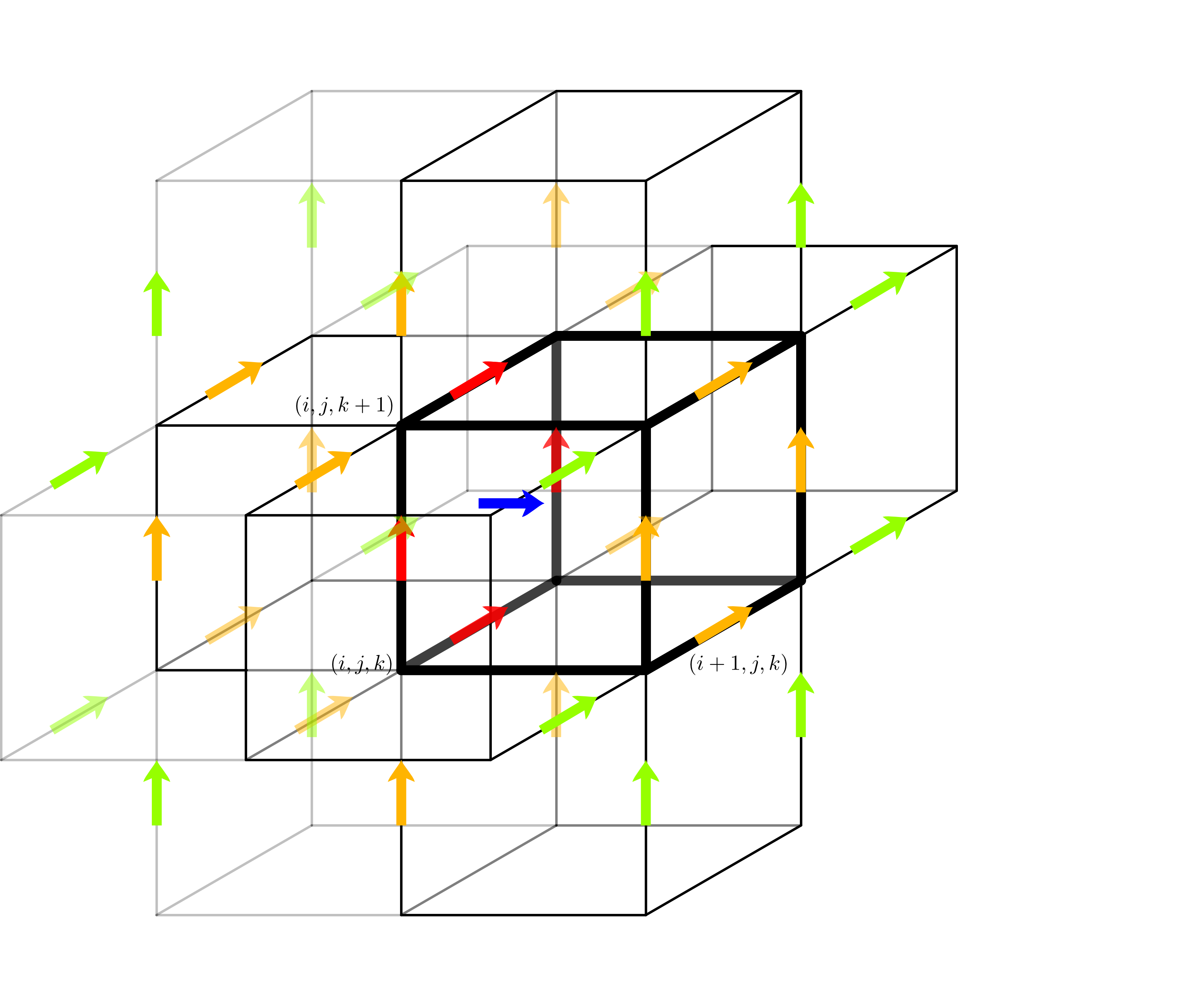

Yee

The code of course implements the standard algorithm by

Yee, 1966 that

also drives the grid layout for the field quantities.

In this algorithm the curl of the electric field that is necessary to

update B_x is computed from the four components of E_y and E_z that

surround B_x in the staggered grid. The algorithm is straight forward

and guarantees that the magnetic field does not gain a non-physcial

divergence.

This algorithm is 2nd order accurate in dx, but is somewhat anisotropic

and exhibits significant numerical dispersion along the coordinate axes.

4th Order

In an attempt to improve the field solver a (naive) solver that is

4th order accurate was implemented. This solver uses additional grid

location of E_y and E_z to compute curl(E) that enters the update of

B_x. The big advantage is that it requires very limited modification

of the code as the same grid layout can be used. The major downside is

that the higher order of convergence is not visible at typical cell

spacings and that smaller cell spacings where the faster convergence

would be beneficial are typically prohibitively expensive.

NSFD (CK, CK5)

The big improvement came with the realization that order of convergence

is not as important as the error constant in front of the leading term.

Here the

non

standard

finite

differences

schemes proposed by

Cole,

1997 and

Kärkkäinen,

2006 excel. They use additional grid locations to compute the curl

and optimize their relative weights to obtain numerical approximations

of the curl operator that combine 2nd order accuracy with other

desirable properties. A paper by

Vay et al., 2011

discusses a number of potential parameters of such NSFD schemes.

ACRONYM implements (in the nomenclature used there) the schemes CK and

CK5, that offer maximally long time steps and maximally isotropic

propagation, respectively.

M24

In another modification of the Yee scheme

Hadi, 1997 has proposed

to use the grid locations used by the Yee scheme, the naive 4th

order solvers and the grid location required to close the big outer

loop. Again different relative weights are possible.

Greenwood et al.,

2004 have shown that a carefully chosen set of parameters can

change the phase speed of electromagnetic waves suitably to remove grid

Chernenkov effects. The scheme is not perfect and can therefore not

remove grid Chernenkov radiation under all conditions, but the common

case of axis parallel beams profits significantly. If Chernenkov

radiation is still an issue the solver can be combined with

Friedman

filtering.

Radiation Free (Darwin)

While the electrostatic plasma model neglects all effects O(v/c) and

the electromagnetic model retains the finite speed of light, it is also

possible to construct a plasma model that retains effects up to

O(v^2/c^2), but ignores higher order effects. Interestingly enough there

is a unique construction that does that which is equivalent to removing

the displacement current and thus removing electromagnetic radiation.

This results in longitudinal fields identical to the electrostatic

plasma model, some transverse electric fields (but no light waves), and

some corrections to the background magnetic field. Unfortunately the

solver is quite complex and follows some unpublished work by Decyk. The

biggest challenge is that the equation for the transverse electric

field E_T needs the temporal change of the current density d j/dt as an

input. Calculating this quantity from standard current deposition is

too noisy. It is possible to rewrite the term, but at the cost of

extra, numerically expensive, deposition steps.

Boundary Conditions

The code in general allows for several boundary conditions, that can

be different for different ends of the simulation domain. (Of course a

periodic boundary at the lower end of the x axis needs to be connected

to a periodic boundary at the upper end of the same axis.) The main

challenge when creating boundary conditions is the need to have full

consistency between the boundary formulation for the electromagnetic

fields and the boundary conditions for the particles. Discrepancies lead

to the formation of charged layers in the best case and violent

instabilities in the worst case. Periodic boundary conditions are the

easiest and most widely supported boundary conditions. Reflective

boundary conditions are only supported by the electromagnetic plasma

model. Absorbing boundary conditions are at least supported by

electrostatic and electromagnetic solvers.

Periodic Boundary Conditions

Periodic boundary conditions are straight forward and are actually

handled internally in the same way as the interior inter-task

boundaries, i.e. particles are sent to the new CPU and field values are

copied into ghost zones. The wrap around is handled transparently by

the geometry of the MPI Cartcom.

Perfect Electric Conductor

Metal walls with perfect electric conductivity are modeled by setting

the tangential electric field to zero. The current densities of

particles close to the metal wall are adjusted using the current of an

imaginary mirror charge on the other side of the wall. Since these

boundary conditions are reflective to electromagnetic waves they are

complemented on the particle side with specular reflection of incident

particles. Unlike a real metal wall no charged particles are absorbed

or reflected.

Absorbing Boundary Conditions

The absorbing boundary conditions are implemented using a perfectly

matched layer. Many different PML formulations exist. The current

implementation uses an unsplit formulation. To improve absorption of low

frequency waves a complex frequency shift approach is used, that

requires a convolutional PML, i.e. the storage of auxiliary fields in

the boundary region. On the particle side, outgoing particles are

simply removed. The injection of new particles is handled by filling

the ghost zone with new particles, performing one timestep inside the

ghost zone and keeping the particles that enter the simulation domain.

Output

Field quantities are written to self-describing HDF5 files in Pixie

format using parallel HDF5 (i.e. one HDF5 file per simulation, for all

CPUs and all timesteps). Particle data can be written to HDF5 tables

or to binary files using MPI-IO.

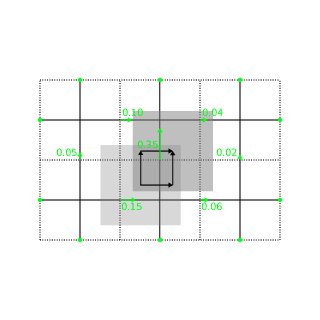

The electric field components are located at grid edges, displaced to

the center of the edge that is aligned with the direction of the field

component. That is the x component E_x of the electric field is

displaced by half a grid spacing dx along the edge e_x.

The electric field components are located at grid edges, displaced to

the center of the edge that is aligned with the direction of the field

component. That is the x component E_x of the electric field is

displaced by half a grid spacing dx along the edge e_x. The magnetic field components are located on the dual grid, that is on

the cell faces. The x component B_x of the magnetic field is located

at the center of the face defined by e_y and e_z.

The magnetic field components are located on the dual grid, that is on

the cell faces. The x component B_x of the magnetic field is located

at the center of the face defined by e_y and e_z. The components of the electric current (and mass flow, if computed for

analysis purposes) are located at the mid points of cell edges.

The components of the electric current (and mass flow, if computed for

analysis purposes) are located at the mid points of cell edges. The charge density is located in the corner of the grid cell. The

center of the grid cell would seem more intuitive, as it would then

represent all charges in the cell, but the location in the corner

makes the formulation of the Poisson equation (for the electrostatic

plasma model) and of the discrete continuity equation (when testing the

electromagnetic plasma model) much easier.

The charge density is located in the corner of the grid cell. The

center of the grid cell would seem more intuitive, as it would then

represent all charges in the cell, but the location in the corner

makes the formulation of the Poisson equation (for the electrostatic

plasma model) and of the discrete continuity equation (when testing the

electromagnetic plasma model) much easier.

While assigning particles simply to the nearest grid point (NGP) is

possible, this trivial zeroth order interpolation introduces too much

numerical noise to be useful. Assigning a finite size of one grid cell

to particles strongly reduces this noise. The overlap integral between

the charge cloud representing the particle and the grid cell (area

weighting) can be calculated analytically beforehand and the resulting

computation is equivalent to a linear interpolation. This CIC method was

originally introduced by

Birdsall and

Fuss, 1969 and made semi-Langrangian plasma simulations feasible.

While assigning particles simply to the nearest grid point (NGP) is

possible, this trivial zeroth order interpolation introduces too much

numerical noise to be useful. Assigning a finite size of one grid cell

to particles strongly reduces this noise. The overlap integral between

the charge cloud representing the particle and the grid cell (area

weighting) can be calculated analytically beforehand and the resulting

computation is equivalent to a linear interpolation. This CIC method was

originally introduced by

Birdsall and

Fuss, 1969 and made semi-Langrangian plasma simulations feasible.

While CIC is a big improvement over NGP, it is not perfect. A widely

discussed (see e.g. chapter 5 in the standard reference Computer

simulations using particles by Hockney and Eastwood, 1988)

improvement is the triangular shaped cloud (TSC) that replaces the

piecewise defined cloud of CIC with a continuous, piecewise linear

function. This increases the effective size of the particle and the

number of grid cells involved in the interpolation somewhat, but the

reduced noise level and the improved isotropy usually justifies the cost.

While CIC is a big improvement over NGP, it is not perfect. A widely

discussed (see e.g. chapter 5 in the standard reference Computer

simulations using particles by Hockney and Eastwood, 1988)

improvement is the triangular shaped cloud (TSC) that replaces the

piecewise defined cloud of CIC with a continuous, piecewise linear

function. This increases the effective size of the particle and the

number of grid cells involved in the interpolation somewhat, but the

reduced noise level and the improved isotropy usually justifies the cost.

The next higher order interpolation function is the piecewise quadratic

shape (PQS), which is not only continuous, but also differentiable. This

improves roll-off of the Fourier transform by 3dB per octave (a function

that has a discontinuity in the nth derivative has a Fourier transform

that rolls of proportional to 1/k^{n+1}). If the additional cost due to

the growing number of grid cells that are involved in the interpolation

is justified depends on the tolerable noise level and the dimensionality

of the problem.

The next higher order interpolation function is the piecewise quadratic

shape (PQS), which is not only continuous, but also differentiable. This

improves roll-off of the Fourier transform by 3dB per octave (a function

that has a discontinuity in the nth derivative has a Fourier transform

that rolls of proportional to 1/k^{n+1}). If the additional cost due to

the growing number of grid cells that are involved in the interpolation

is justified depends on the tolerable noise level and the dimensionality

of the problem.

The default current deposition scheme follows the method proposed by

Esirekepov,

2001. It decomposes the particle motion into axis parallel motions

that are weighted in such a way that the correct total current is

produced and charge conservation is satisfied. This method works with

all shape functions and shows good performance.

The default current deposition scheme follows the method proposed by

Esirekepov,

2001. It decomposes the particle motion into axis parallel motions

that are weighted in such a way that the correct total current is

produced and charge conservation is satisfied. This method works with

all shape functions and shows good performance.

Alternatively the code also supports the current deposition algorithm

by Umeda,

2003. This algorithm decomposes the particle motion into straight

segments with the constraint that the particle can only cross cell

boundaries at the middle of cell faces. Only CIC and TSC shape

functions are supported. It should be possible to extend this to other

shape functions, but to our knowledge this is beyond the published

state of the art. Main advantage of the deposition method is a

different distribution of numerical noise in k-omega space that might

be advantageous to some simulations.

Alternatively the code also supports the current deposition algorithm

by Umeda,

2003. This algorithm decomposes the particle motion into straight

segments with the constraint that the particle can only cross cell

boundaries at the middle of cell faces. Only CIC and TSC shape

functions are supported. It should be possible to extend this to other

shape functions, but to our knowledge this is beyond the published

state of the art. Main advantage of the deposition method is a

different distribution of numerical noise in k-omega space that might

be advantageous to some simulations.

The code of course implements the standard algorithm by

Yee, 1966 that

also drives the grid layout for the field quantities.

The code of course implements the standard algorithm by

Yee, 1966 that

also drives the grid layout for the field quantities. In an attempt to improve the field solver a (naive) solver that is

4th order accurate was implemented. This solver uses additional grid

location of E_y and E_z to compute curl(E) that enters the update of

B_x. The big advantage is that it requires very limited modification

of the code as the same grid layout can be used. The major downside is

that the higher order of convergence is not visible at typical cell

spacings and that smaller cell spacings where the faster convergence

would be beneficial are typically prohibitively expensive.

In an attempt to improve the field solver a (naive) solver that is

4th order accurate was implemented. This solver uses additional grid

location of E_y and E_z to compute curl(E) that enters the update of

B_x. The big advantage is that it requires very limited modification

of the code as the same grid layout can be used. The major downside is

that the higher order of convergence is not visible at typical cell

spacings and that smaller cell spacings where the faster convergence

would be beneficial are typically prohibitively expensive.

The big improvement came with the realization that order of convergence

is not as important as the error constant in front of the leading term.

Here the non standard finite differences

schemes proposed by Cole,

1997 and

Kärkkäinen,

2006 excel. They use additional grid locations to compute the curl

and optimize their relative weights to obtain numerical approximations

of the curl operator that combine 2nd order accuracy with other

desirable properties. A paper by

Vay et al., 2011

discusses a number of potential parameters of such NSFD schemes.

ACRONYM implements (in the nomenclature used there) the schemes CK and

CK5, that offer maximally long time steps and maximally isotropic

propagation, respectively.

The big improvement came with the realization that order of convergence

is not as important as the error constant in front of the leading term.

Here the non standard finite differences

schemes proposed by Cole,

1997 and

Kärkkäinen,

2006 excel. They use additional grid locations to compute the curl

and optimize their relative weights to obtain numerical approximations

of the curl operator that combine 2nd order accuracy with other

desirable properties. A paper by

Vay et al., 2011

discusses a number of potential parameters of such NSFD schemes.

ACRONYM implements (in the nomenclature used there) the schemes CK and

CK5, that offer maximally long time steps and maximally isotropic

propagation, respectively.

In another modification of the Yee scheme

Hadi, 1997 has proposed

to use the grid locations used by the Yee scheme, the naive 4th

order solvers and the grid location required to close the big outer

loop. Again different relative weights are possible.

Greenwood et al.,

2004 have shown that a carefully chosen set of parameters can

change the phase speed of electromagnetic waves suitably to remove grid

Chernenkov effects. The scheme is not perfect and can therefore not

remove grid Chernenkov radiation under all conditions, but the common

case of axis parallel beams profits significantly. If Chernenkov

radiation is still an issue the solver can be combined with

Friedman

filtering.

In another modification of the Yee scheme

Hadi, 1997 has proposed

to use the grid locations used by the Yee scheme, the naive 4th

order solvers and the grid location required to close the big outer

loop. Again different relative weights are possible.

Greenwood et al.,

2004 have shown that a carefully chosen set of parameters can

change the phase speed of electromagnetic waves suitably to remove grid

Chernenkov effects. The scheme is not perfect and can therefore not

remove grid Chernenkov radiation under all conditions, but the common

case of axis parallel beams profits significantly. If Chernenkov

radiation is still an issue the solver can be combined with

Friedman

filtering.